“Ānanda, I am now old, worn out, venerable, one who has traversed life’s path, I have reached the term of life, which is eighty. Just as an old cart is made to go by being held together with straps, so the Tathagata’s body is kept going by being strapped up. It is only when the Tathagata withdraws his attention from outward signs, and by the cessation of certain feelings, enters into the signless concentration of mind, that that his body knows comfort.

“Therefore, Ananda, you should live as islands unto yourselves, being your own refuge, with no one else as your refuge, with the Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as your refuge, with no other refuge.”

—[DN 16.2.25-2.26]

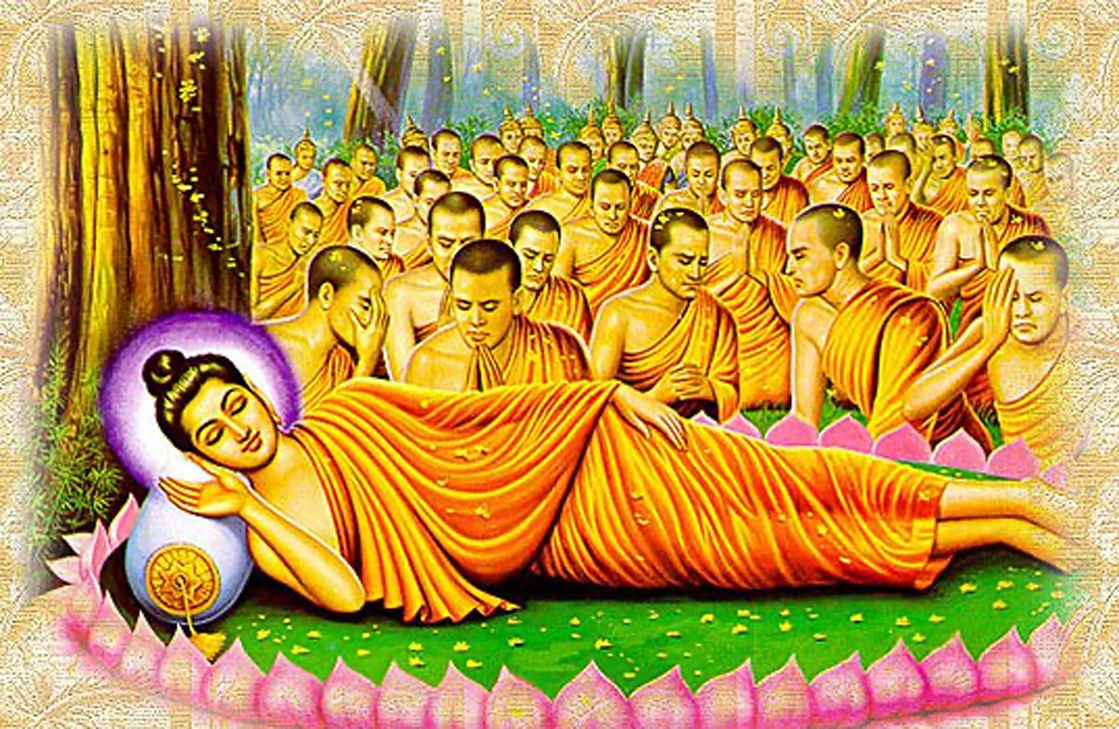

As Bhikkhu Bodhi has pointed out, the purpose of the Pāli Canon is to share the teachings of the Buddha, not to be biographical. However, there are several places in the Canon where there are lengthy descriptions of chapters in the Buddha’s life. The story of his passing is one of them. The story of his passing is in the Mahāparinibbānasutta, “The Great Passing—The Buddha’s Last Days,” —[DN 16].

You should read the entire sutta. It covers about the last 18 months of the Buddha’s life. But let me point out a few items of note.

This sutta, perhaps more than any other, is commonly considered to have changed a lot over the centuries. One scholar I know calls it a cut-and-paste job. That may be a little derogatory, but I think you get the idea. Having said that, if you read a lot of the Pāli Canon, any passages that are suspect will be clear.

There is one particular passage that even casual readers will point out, and that is the story about Ānanda. In this story, it is suggested that Ānanda could have prevented the Buddha’s death by asking him to live longer.

Perhaps the most unpopular decision made by the Buddha during his life was his choice to ordain women. That continues to this day, and as a result, passages of misogyny have been inserted into the Canon by misbehaving monks. There is a good description of this problem in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s introduction to his translation of the Aṇguttara Nikāya. And Ānanda, as a champion of the bhikkhuni Saṇgha, became a favorite punching bag of sexist monks. Therefore, it is widely assumed that this passage was inserted to discredit Ānanda.

But as you can see from the above quote, the Buddha was falling apart physically. It is unlikely he would have chosen to continue even if he could.

Another item of note is the second paragraph in the above quote. The Buddha famously refused to appoint a successor. Instead, he said that the Dhamma should be your teacher:

“But, Ananda, what does the order of monks expect of me? I have taught the Dhamma, Ananda, making no ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ the Tathagata has no ‘teacher’s fist’ in respect of doctrines. If there is anyone who thinks: ‘I shall take charge of the order’, or ‘The order should refer to me’, let him make some statement about the order, but the Tathagata does not think in such terms. So why should the Tathagata make a statement about the order?”

—[DN 16.2.25]

As you can see here, the Buddha states that there was no “teacher’s fist,” meaning that he held nothing back. This is important because later traditions of Buddhism sometimes claimed that they had found “hidden teachings.” But here the Budda specifically refutes that claim.

The Buddha did not want any person, even his most trusted disciple, to be in charge of the Saṇgha.

I know a monk who says that your favorite teacher should be the Buddha. Traditionally it is believed that the Buddha knew more than anyone else. I think that is true. Every disciple knew something, and some of them knew a lot. But only the Buddha knew it all.

You will find this in your own practice. There are parts of the Dhamma to which you will feel connected, and there are parts that never connect with you. This is the way the Dhamma is. Even the Buddha’s most respected disciples like Sāriputta and Moggallāna did not have the Buddha’s full understanding of the Dhamma.

Further, be careful about who you accept as a teacher. The Buddha addresses this in the Cūḷahatthipadopama Sutta “The Shorter Discourse on the Simile of the Elephant’s Footprint”, MN 27. He gives a lengthy description of how you can know a true teacher.

The truest teacher is the Buddha himself. I am often distraught at how many people claim to be Dhamma teachers, yet they have not read a single volume of the Pāli Canon, and I mean cover-to-cover. That would be like a Christian minister who has not read the New Testament or a Rabbi who has not read the Tora or an Imam who has not read the Koran. That would be unthinkable, and yet it is the normal case in Buddhism, especially Western Buddhism. How can you know the Dhamma if you have not read and studied it?

Too many teachers are guilty of “cherry picking.” They know a few suttas. They can quote from them well. But they use these few suttas to support their own conditioning and beliefs. I once took a one year course taught by two teachers. The one who was supposed to teach the Dhamma did not believe in rebirth. The one who was supposed to teach meditation did not practice jhāna. Mercy.

Teachers are important, of course. But sadly, a lot of Buddhism is guilty of “creeping Hinduism,” and that is the notion of a guru. A “guru” is someone who is supposed to “impart transcendent wisdom.” But that is not what the Buddha taught. Your awakening is up to you. A guide can point the way. But even the Buddha could not “impart transcendent wisdom.” Each individual must realize awakening for him or her self.

Trust your teachers. Be grateful for them. But your true teacher is the Buddha. Trust in him and trust in the Dhamma. And most importantly, trust in yourself.

Happy Vesak and happy travels.

“Then the Lord said to the monks: ‘Now, monks, I declare to you: all conditioned things are of a nature to decay — strive on untiringly.’ These were the Tathāgata’s last words.” —[DN 6.7]